Test Tube Babies

Season 19 Episode 4 | 50m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Researchers face controversy while conceiving babies through in vitro fertilization.

Pioneering researchers attempting to conceive babies through in vitro fertilization faced daunting obstacles and much controversy before the world's first test tube baby was born on July 25, 1978.

Corporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Test Tube Babies

Season 19 Episode 4 | 50m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Pioneering researchers attempting to conceive babies through in vitro fertilization faced daunting obstacles and much controversy before the world's first test tube baby was born on July 25, 1978.

How to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

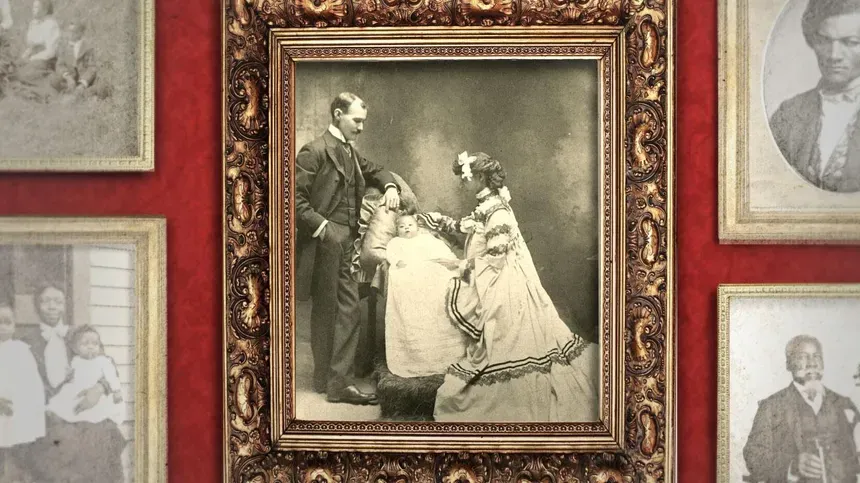

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ NARRATOR: On September 12, 1973, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a 29-year-old woman was wheeled into an operating room at New York Hospital.

A surgeon made an incision into her abdomen and withdrew an egg from her ovary.

If the procedure went as planned, Doris Del-Zio would become the first woman in the world to conceive a baby through in vitro fertilization, or IVF.

The surgeon put the egg in a test tube and went to find Doris's husband.

And I waited until he had... had the egg in the tube, and he had put the nutrients in, and he had sealed it, and he gave it to me.

He says, "Get to Dr.

Shettles."

I took the test tube, and I put it under my arm to keep it warm, I thought, and I went over to Columbia by cab.

NARRATOR: 15 minutes later, John Del-Zio arrived at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

Waiting for him in the lobby, near the men's room, was the country's foremost expert on IVF, Dr. Landrum Shettles.

DEL-ZIO: And he said, "Now, you take this other tube, go into the men's room..." (chuckles) "and get me some sperm."

So that's what I had to do.

And I went in and got the sperm.

Brought it out to him, handed it to him, and he says, "Okay, I'll call you at the hospital tonight."

NARRATOR: Shettles headed straight to a lab on the 16th floor.

♪ ♪ After years of frustration and disappointment, he believed he was about to make history.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Back in the 1930s, Harvard scientists had mastered in vitro fertilization in rabbits.

But the human egg refused to yield its secrets.

Nobody had seen a human embryo.

In fact, the earliest stages of human embryogenesis had never been seen.

They were just a figment of our imagination.

We assumed they existed, because we assumed that human reproduction was the same as reproduction in other mammals.

NARRATOR: The Harvard experiments attracted the attention of John Rock, one of the nation's leading fertility specialists.

Rock was quick to see IVF's potential to help infertile women.

In 1938, he hired researcher Miriam Menkin-- who had experience with IVF in rabbits-- to begin experimentation in humans.

MARGARET MARSH: Several hundred women had agreed to have their eggs used for fertilization.

No success.

Week in, week out, no success.

Trying all these different techniques-- no success.

NARRATOR: Over the next six years, she recalled, failure became routine.

Tuesday, Menkin would hunt for eggs in ovaries removed from Rock's surgical patients.

Wednesday, she would mix the egg with sperm donated from medical students.

On Thursday, she would pray.

Then, on Friday came disappointment-- no fertilization.

On the morning of February 6, 1944, Menkin's routine was finally broken.

MARSH: She had a teething baby at home, she was up for two nights running.

She went into the lab, she did her fertilization, and she was watching the sperm attack the egg.

She was watching the sperm go round and round and round.

And she was tired.

She felt like she couldn't get up.

So she exposed the egg to the sperm for a longer period of time.

NARRATOR: When Menkin looked into her microscope, she was stunned to see a two-cell fertilized egg.

Miriam Menkin, when she saw the first fertilized egg, was absolutely awestruck.

It was, she said, the most profound sight in the world.

She was unable to take her eyes from it.

NARRATOR: News of the achievement spread quickly and the press coined the term "test tube baby."

The response shocked John Rock.

Infertile women inundated him with letters begging for the promising new technology.

But just as the path-breaking research was getting off the ground, Rock received devastating news.

Miriam Menkin told him she was leaving to follow her husband to his new job in North Carolina.

Without Menkin, the project floundered, and John Rock soon abandoned the experiments.

IVF research came to a standstill.

♪ ♪ For many Americans in the 1950s, the prospect of "test tube babies" seemed ripped from the pages of science fiction novels.

MARSH: Nobody knew what would happen when you put human sperm and a human egg in a dish and then you grew it and you implanted it in a woman's uterus.

Nobody knew what would happen.

There was a cadre of people who thought this is just going beyond what is appropriate for scientists, that this is treading on the work that belongs only to God and nature.

NARRATOR: But Landrum Shettles saw things differently.

He was convinced in vitro fertilization was the next scientific frontier.

♪ ♪ HENIG: Shettles seemed to have almost an obsession with human eggs.

He actually slept in his office.

He had seven children and a wife in some little apartment on Claremont Avenue in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and he chose to stay up on 168th Street in the hospital.

And in the middle of the night, he would just sort of be around, be in the hallways with his white coat flapping behind him.

GEORGIANNA JAGIELLO: I would see him in the hall in his scrub greens at all hours of the day and night.

He was a sort of mystical figure in the department.

Nobody really seemed to relate to him, particularly, nor did he reach out very much to us in the research wing.

NARRATOR: In 1955, Life magazine reported that Shettles had managed to fertilize a human egg and keep it alive for three days.

The 46-year-old scientist made an unlikely public figure.

Shettles had a thick Mississippi accent from his... his farm boy days, and he kind of looked like... One of his colleagues called him a large version of Truman Capote.

And his manner was strange because he didn't look people in the eye.

He was... he was awkward.

He had some of the earmarks of what you would think of as a genius.

He couldn't quite live in this world.

NARRATOR: In 1960, Shettles published "Ovum Humanum," a photographic atlas showing microscopic human eggs-- called oocytes-- in early stages of development.

JAGIELLO: They were unique.

Here were human oocytes.

Sperm, one had seen, but many of us had worked with mice and cows and sheep and monkeys and species of that sort, but to see human was very exciting; really thrilling photographs.

NARRATOR: Throughout the 1960s, Shettles struggled to grow an embryo until it was large enough to reinsert into the womb.

Then, in 1969, he was stunned to learn that two British researchers were racing ahead of him.

After a series of breakthroughs, physiologist Robert Edwards and gynecologist Patrick Steptoe were ready to implant embryos into women's bodies.

♪ ♪ Test tube babies were no longer a fantasy.

They were on the horizon.

Many Americans were horrified.

The idea that you could take a human embryo which you've created in the Petri dish, which is already very unnatural and abnormal, and then take that embryo and put it back into a woman's uterus and have a baby born was appalling to most people.

Even to scientists and most other doctors, it felt uncomfortable.

HENIG: There was a real belief that if you were going to mess around with eggs and sperm in a Petri dish and make a baby, that you could do some real chromosomal damage and create monsters.

Even testing in animals wouldn't really, at the end, tell us whether this would be safe in humans.

So there were some people who were warning that we simply shouldn't go down this road.

Many people were concerned, "Will we come to see "the technological production of children "as, in fact, superior in the long run, "because in the newfangled Brave New World, "we will be in a position to ensure that unhealthy or imperfect children are not born?"

Well, I think there was a fear of the slippery slope-- that if it would work for infertile couples, then maybe people would start to say, "Hey, I'd like to have a smart baby, or an athletic baby, or some other desirable kind of traits in my baby," and if you could pick the sperm and the egg, then maybe that's the way that we'll all have babies.

It was about eugenics.

It was about making super babies, perfect babies, better babies.

NARRATOR: In Washington, federal agencies placed an unofficial moratorium on IVF funding.

The progress of IVF in America, of course, was greatly impeded by the fact that the National Institutes of Health, the greatest granting agency there is, or at least with the greatest amount of money, would not entertain any applications for IVF.

It was clear that IVF opponents prevented federal funding for IVF.

NARRATOR: At Columbia Presbyterian, administrators grew increasingly concerned that Shettles' research might jeopardize the hospital's reputation.

This was a very conservative place.

It prided itself on being, uh, let's put it this way, not first to get there, but maybe second to get there, but that was okay because the people who got there first didn't always know what they were doing.

NARRATOR: Shettles' superiors repeatedly warned him not to cross the line into human experimentation.

If any one individual does research that goes against some regulation, like, does human research without asking for permission, then all the federal grants are endangered.

NARRATOR: The job of protecting Columbia Presbyterian's interests fell to Dr. Raymond Vande Wiele, chair of the ob-gyn department.

CAPLAN: Ray Vande Wiele was very conservative, strongly oriented toward moral values, particularly religious values.

This is a guy who is the captain of the ship.

He was a guy who was large and in charge.

NARRATOR: Vande Wiele demoted Shettles to a low-profile position with few responsibilities.

But Landrum Shettles was not easily deterred.

He still had access to a lab and continued his IVF research.

Great scientists, he believed, advance science by defying conventional thinking.

(people clamoring) In January 1973, the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade to legalize abortion and unleashed one of the most polarizing debates in the nation's history.

The course of IVF in America would now become entangled with the controversy over the status of the embryo.

It seems that in order to achieve a successful fertilization in vitro in the laboratory, a number of fertilized ova must be there, and, of course, only one is going to go through the process of embryo transfer into the uterus.

Now, what do you do with these discards?

What are they?

So when the subject came up to do in vitro fertilization, you might have to do research on an embryo, that immediately raised the question, "Well, what is an embryo?"

That immediately raised the question, "When does life begin?"

MARSH: You have increasingly vocal anti-abortion forces saying in order to create an embryo that you might be able to transfer into a woman's uterus, you have to destroy all these embryos on the way to doing research, and you're engaging in murder.

NARRATOR: Opponents of abortion began pressing the federal government to ban embryo research.

Landrum Shettles believed it was now or never.

If he didn't act quickly, the government might move to prohibit IVF.

That fall, he agreed to try the procedure on a couple from Florida.

Doris and John Del-Zio had been married for five years.

Doris had a daughter from her first marriage.

Still, she wanted a child with John.

JOHN: I felt that the bad portion of life was behind me and that we've got something ahead that we might look forward to and make a future of it for both of us.

We were both divorced.

I thought this might be the time to start fresh.

NARRATOR: But a ruptured appendix had left her fallopian tubes mangled and scarred, leaving Doris infertile.

DORIS: When they tell you that you are incapable of conceiving a child, it's horrible.

I'm not giving John a child.

It's my failure.

It's not John.

It's my failure.

NARRATOR: Doris underwent three painful surgeries to open her damaged tubes.

Each attempt failed.

Her surgeon, Dr. William Sweeney, urged her to stop.

DORIS: He said, "I really think you're crucifying yourself with all this surgery you're doing."

He said, "I know you want a baby, "but you've got to accept the fact that you just can't have a child."

And I just could not accept that fact.

NARRATOR: Reluctantly, Sweeney decided to tell Doris about Landrum Shettles and the risky, new procedure he was developing to bypass damaged fallopian tubes.

Shettles could take an egg extracted from her ovary, fertilize it in a Petri dish, and return it to her uterus.

As a child, I had polio, and I always believed that because of the doctors helping me overcome the polio, that they were put up on a pedestal and that they can do anything, and that they were able to help me walk again and live a normal life; that they were going to help me with this.

We thought that this guy is the guy, this is the man that's going to make a success of what we wanted, and we thought nothing about not going ahead with it.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Landrum Shettles told no one at Columbia Presbyterian he was proceeding with an experiment in human IVF.

Alone in a 16th-floor lab, he mixed Doris's egg and John's sperm in a test tube and placed it in an incubator set to 98 degrees.

Later that day, a young scientist unexpectedly entered the lab.

She saw this unusual test tube that looked kind of dark-brown red with a red stopper, which meant it was a chemical test tube, nonsterile.

And she came to my office and said, "I want you to look at this "because I don't know what this is and perhaps it shouldn't be there."

NARRATOR: At 8:00 a.m. the following morning, Raymond Vande Wiele learned of the experiment taking place down the hall from his office.

Vande Wiele was enraged.

CAPLAN: I can't imagine that Vande Wiele wasn't freaking out that if this experiment hit the papers, that it could adversely impact Columbia's funding, it could get some sort of legal authorities in there to say, "What are you doing, making this thing in the lab?"

and that the PR alone could be damaging to the department.

NARRATOR: Vande Wiele ordered a staff member to remove the test tube from the incubator, knowing it would destroy the specimen.

Then, he went searching for Shettles.

CAPLAN: I happened to be in the hallway up where ob-gyn was, and all of a sudden here comes Landrum Shettles flying down the hallway at almost a run-- if not running, then close-- and he zooms around the corner.

And I'm sort of, "Whoa, what was that?"

And he's trailed within 30 seconds by Raymond Vande Wiele, who's a much bigger guy, and this is more like a large semi coming down the hallway at a pretty fast clip.

And he's red-faced, and he's mad, and he's muttering.

And he goes whipping around the corner, clearly after Shettles.

NARRATOR: When Vande Wiele caught up with him, Shettles knew his career at the hospital was over.

The maverick scientist was forced to resign.

♪ ♪ Several hours later, John Del-Zio was called away from his wife's bedside to take a phone call from Dr. Sweeney.

And Dr. Sweeney says, "Somebody at Columbia "removed the test tube from the incubator, and we have to abort the whole thing."

I said, I-I-I asked him, "No part could be salvaged?"

He said, "No, no, it's... just forget about the whole thing."

And we were both stunned.

And he said to me, Dr. Sweeney said to me, "I don't know what to tell her."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: As evening settled over the city, Doris lay alone in her hospital room.

The phone rang.

It was Landrum Shettles.

DORIS: He said, "I'm so sorry, Doris."

He said, "I can't believe they did this."

And I said, "Who did what?"

He said, "You don't know?"

And I said, "No.

What are you talking about?"

He said, "Dr. Vande Wiele destroyed the specimens."

And I said, "No!

No!

It couldn't... it couldn't... they couldn't... they couldn't."

And I just lay there all night.

And I couldn't sleep.

And I'm just laying there crying.

And early the next morning before daybreak, the door opened and Dr. Sweeney walked in... And he came over and he just held me, and just let me cry.

That was the end of my... my dream.

And it was the beginning of a nightmare.

(engine roars) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Back home in Florida, Doris Del-Zio could not let go of the past.

She was aloof, didn't want to even have anything to do, er, uh, sexually, you know.

And for a long period of time, she was affected in that way.

Uh... She felt that she wasn't a woman anymore.

NARRATOR: Then, John received a call from Landrum Shettles.

And Dr. Shettles explained to me that if we don't do something to show that we had opposed the actions of Dr. Vande Wiele, then perhaps experimentation on procedures like this could not go on in the United States in the future.

And I was really upset about this at this point, because I didn't want to go to a lawsuit.

I said, "John, I can't face it."

And he said we have a lawsuit.

But they couldn't do it without me.

NARRATOR: The Del-Zios sued Columbia Presbyterian for a million and a half dollars, accusing Raymond Vande Wiele of inflicting severe mental pain and anguish.

The progress of IVF in America was about to shift from the lab to the courtroom.

♪ ♪ In England, Edwards and Steptoe were transferring fertilized eggs back into the mother's body.

But the embryos wouldn't take.

One, two, ten, 100 transfers-- and no pregnancies.

JONES: The problem was many times you changed two or three things, and then if you got a little inkling that something was working, you weren't sure which one it was.

So that it became a very troublesome trial-and-error sort of thing to get all these little technical details right.

NARRATOR: For nearly a decade, the pair persevered without government funding.

Then, in November 1977, they achieved a successful pregnancy for a factory worker named Lesley Brown.

The fate of IVF would rest on the health of this baby.

While the world waited for the arrival of the first test tube baby, the Del-Zios' lawsuit finally came to trial.

DORIS: I was stunned.

The whole street was closed off.

There were TV trucks and cameras all over the place.

There were people running after me.

I didn't know where they were coming from.

It was like a mob scene.

And they were all running at me with-with microphones.

The court was completely packed with people from all over the world: from South America, from China, from Japan.

I couldn't believe it!

I could not believe it.

I sat there completely stunned.

NARRATOR: The press dubbed the Del-Zio case "the test tube baby death trial."

REPORTER: How are you feeling?

Nervous and hopeful.

REPORTER: The defense... the defense is saying that this procedure would have endangered your life.

Do you agree with that?

No comment.

No comment.

I'm sorry.

Dr. Shettles has no comment.

No comment.

HENIG: The Del-Zios said that something had been done to them by Raymond Vande Wiele and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

And the defense chose instead to put on trial Landrum Shettles.

How do you feel about the baby?

We have no opinion about the matter.

Thank you.

Please let the doctor through.

HENIG: He was presented as a once-promising scientist who couldn't do his work anymore, who was taking shortcuts, and who was so inept that he couldn't possibly have been actually growing an embryo in there.

REPORTER: The defense claims the procedure was a Model-T operation.

How do you defend your handling of it?

Well, I think that Mr. Lindbergh flew the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis.

I can't compare the Spirit of St. Louis with a 707, but he got to Paris.

If Mr. Lindbergh, sitting out there in Long Island, if his airplane had been destroyed before he took off, he couldn't have gotten to Paris.

And that's exactly what happened to us.

We had an airplane sitting up there, ready to fly to Paris, and somebody destroyed it.

NARRATOR: Once the trial began, Vande Wiele's attorneys called Doris to the stand.

For the next three days, she was grilled by a battery of lawyers.

They're defending Columbia, the giant.

And here we were, defending me and Doris.

It was like David and Goliath.

HENIG: And at one point, one of the lawyers says, "Why did you even file this lawsuit?"

She said, "I didn't want this to happen again."

And he said, "You mean, you... you didn't want to allow the kind of rash experimentation that Landrum Shettles did?"

Which was, of course, the defense, you know, this was all rash experimentation.

And she said, "No, I didn't want anyone else to have a Dr. Vande Wiele kill their baby."

You know, "You killed my baby."

The... her response all the time was, "That was going to be my baby and you killed my baby."

HENIG: And there was sort of a hush in the courtroom, and the lawyer said, "You don't mean that.

You didn't think that was a baby."

And she said, "Yes!

It was.

He killed my baby."

To this day, it was my baby.

It'll always be my baby.

I don't know which baby it was, but it was my baby.

NARRATOR: On July 25, 1978, nine days into the trial, the drama in the courtroom was overshadowed by events in England.

Good evening.

The first baby ever conceived outside the mother's body was born in England-- the so-called "test tube baby," born by cesarean section.

It is a girl, in excellent health.

A beautiful, normal baby, the doctors said.

And they said this may open the way for some, though not all, women who cannot have children otherwise.

(newborn wailing) NARRATOR: With the birth of Louise Joy Brown, Edwards and Steptoe had pried open the mystery of human reproduction that had eluded Landrum Shettles.

DORIS: I guess I'll always wish that was my baby.

I'll always want my child.

And it does hurt a little bit to know that I'll never be able to have a baby, but it can't take away from the joy I feel for Mrs. Brown today.

Well, we're overjoyed, overjoyed, for Mrs. Brown, of course, and for science, which is what we're talking about mostly now.

I was very angry.

I says, "We didn't... We're not the first in this country to do it," because I was thinking in terms of the United States being the first to do something like this.

And I was angry at first, and I said, "Well, I hope that this will show the jury "that it's possible, that we certainly can win this case now."

(crowd clamoring) NARRATOR: After a month-long trial, the jury found Raymond Vande Wiele guilty of wrongfully causing emotional distress, but awarded the Del-Zios only $50,000 in damages-- a fraction of their request.

I think the court, when it tried to wrestle with the question of what to do, didn't know how to compensate for a hypothetical.

Maybe there had been an embryo made.

Maybe that embryo could have become a baby.

Maybe that baby would have been normal.

That's a lot of maybes, and courts don't like to award a lot of money on the basis of a lot of maybes.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Shettles never regained his reputation and the Del-Zios never had a baby, but the trial forced Americans to grapple with their conflicted attitudes toward in vitro fertilization.

♪ ♪ (applause) How would you like to be the world's first test tube baby?

What do you do on Father's Day?

You send a card to the DuPont Corporation?

(laughter) I understand after the baby was conceived in the laboratory, a pair of beakers smoked a cigarette and stared at the ceiling.

(typewriter keys clacking) A test tube baby, yes, indeed.

Both mother and baby are doing very well indeed.

HENIG: She was on the cover of every magazine and every newspaper, and she was called "the baby of the century," and it was an incredible circus around the birth of Louise Brown, because... people had been so sure that she was going to be a monster, that when she turned out to be just this chubby-cheeked, blonde newborn who was quite beautiful, there was so much relief.

PHIL DONAHUE: We clearly have a beautiful, beautiful and normal baby.

You couldn't get in your home when you came home from the hospital with the baby.

That's right, yes.

Because of the press?

Press.

Uh... people wanting to see Louise.

Because everybody got the wrong impression.

What was the wrong impression, Mr. Brown?

Well, when they say "test tube baby," everybody had the impression that she was going to be about nine foot tall and about a quarter-inch wide-- you know, something kind of out of, you know, out of a-a comic strip sort of thing.

Yes.

And they were very, very surprised when they seen her.

CAPLAN: Who knew whether the next ten babies were going to turn out to have birth defects and be stillborn and have all kinds of problems?

Nobody.

But the appearance of this clearly healthy, happy kid basically silenced the critics.

NARRATOR: In America, attitudes shifted quickly.

Across the country, infertile couples began to clamor for in vitro fertilization.

In response, critics of IVF stepped up pressure on Washington.

The idea of IVF started to spread in 1980.

1980 is the year that Ronald Reagan became president, and one of Reagan's constituencies was the conservative, religious Republicans, and so Reagan made sure that there would be no federal funding for any research on human embryos.

NARRATOR: Politicians scrambled to placate both sides.

If it could move forward without federal involvement, I think most people in Congress and the state legislatures were ready to say, "God bless it.

It's off my desk."

It wasn't that IVF was banned; it was just that federal funds couldn't be used.

So it was a very clever political ploy in the United States.

It could be done freely in private enterprise, but we weren't going to use any government funds and so the government was being more "ethical" that way.

And that's the way the entire history of IVF began in the United States.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: IVF in America would start up again with two physicians on the verge of retirement.

Drs.

Howard and Georgeanna Jones were leading experts in reproductive medicine at Johns Hopkins.

Even Robert Edwards had sought the couple's advice.

All that was behind them.

JONES: Now, when Georgeanna and I had to retire, the question was: What do we do?

Do we go fishing?

We consulted our children-- and we have three children-- and they unanimously voted that we should go fishing.

NARRATOR: The Joneses were ready to settle into a quiet academic life in Norfolk, Virginia, when their plans were up-ended by the birth of Louise Brown.

The reporter from the local newspaper came to our home on the day that Louise Brown had been born.

While we were moving in, she interviewed us about this nice thing had happened.

We gave her all sorts of good information about that, and then, as she was leaving, she said, "Could this be done in Norfolk?"

And it sounded like a flip question, and I gave her a flip answer.

I said, "Of course."

And she said, "What would it take?"

And I said it would take some money.

And as a result of that, a former patient called up and said, "I see by the paper you need some money.

How much do you need?"

And I had never been asked that question before, and I don't think I've ever been asked that question since.

NARRATOR: The Joneses soon announced their plan to open an IVF clinic.

Anti-abortion activists in Norfolk immediately rallied their forces to stop them.

ANNOUNCER: This is News 3.

REPORTER: Charles Dean is president of the Tidewater chapter of the Virginia Society for Human Life.

Dean claims that fertilized eggs have and will be destroyed by doctors in the clinic.

Basically, the manipulation and destruction of human beings, tiny human beings at their earliest stage, is... has to be unacceptable to any civilized society.

REPORTER: Dr. Howard Jones, who heads up the in vitro clinic, says that doctors plan to re-implant all fertilized eggs, not destroy them.

But fertilization, whether natural or in vitro, isn't perfect, he says, and in those cases, abortion will be offered as an alternative.

It seems to me that it would be... um, unwise and indeed, um... even malpractice not to offer these women the same opportunity that patients who are normally pregnant have.

NARRATOR: Anti-abortion groups found it hard to fight a technology that enabled couples to have a baby.

The momentum was now on the side of IVF.

CAPLAN: If you get babies and they're the biological offspring of those couples, and those couples don't have many other options, I think most Americans say, "Who cares?"

Test tube baby technology is seen by almost every American as pro-life technology.

NARRATOR: On March 1, 1980, the first in vitro fertilization clinic in America opened its doors.

Thousands of women flooded the Joneses with letters, phone calls, and telegrams, begging for the procedure.

In the two years following the birth of Louise Brown, there had been numerous attempts at IVF around the world, but only two more successes.

The science of in vitro fertilization was still in its infancy.

LUCINDA VEECK GOSDEN: In the beginning, the lab was a bit of a black box.

We didn't have a manual to follow.

There hadn't been a number of published papers to that point showing us "do this, push that, collect this, do that."

We had to learn very much on our own through trial and error.

NARRATOR: To start, seven couples arrived in Norfolk from across the country.

Following Robert Edwards' model, the Joneses began tracking the women's menstrual cycles.

They're all elevated over the normal, and we know that... GOSDEN: In that first year when we were working with natural cycles, we were forced by the patients' reproductive biology to collect eggs when their bodies said it was appropriate.

So quite often we were at the hospital at 1:30 in the morning, 4:00 in the morning.

JONES: One of the first things was that we weren't sure we were going to get the egg-- the egg.

And I recall going back to the office after each time, and as I'd walk in the office, the girls in the office said, "Did you get it?"

That would be the question, and most of the time we had to say no.

NARRATOR: A year later, there were still no pregnancies.

The Joneses were stymied.

JONES: We sought the advice of everybody we could.

One of our colleagues said, "You need to work in the dark.

You must remember that the sperm and egg have never seen light."

And therefore, when we began, we did indeed use infrared lights.

Well, that turned out not to be the case.

The sperm and egg have no light receptors and they don't know whether it's light or dark.

But this is the type of technical thing-- and I'm sure I could make a list of 50 of these little technical details-- that had to be worked out.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The turning point came when Georgeanna Jones started using hormones to stimulate her patients' ovaries to produce more eggs.

♪ ♪ Her decision to begin using hormones was a great boon to our patient population, because instead of having a single oocyte that we would hope would become fertilized, we now had two or three we could work with in the laboratory, and thus the chances for our patients were much greater.

NARRATOR: A young couple from Massachusetts, Judy and Roger Carr, were among the first to try the new method.

Months earlier, Judy had nearly died when an embryo lodged itself outside her uterus.

During emergency surgery, her fallopian tubes were removed, leaving her infertile.

My physician walked into the room with a brochure, waving it, saying, "Well, I don't know if you're interested in anything like this, but..." He said, "It's some husband and wife, "and they're starting something new "for couples that can't conceive children.

So, you might want to look into it."

NARRATOR: In March 1981, Judy began a regimen of three hormone shots a day.

Weeks later, two of her eggs were retrieved and one fertilized.

Dr. Jones cautioned the Carrs not to get their hopes up.

I remember him asking us specifically, "Are you... are you a betting... betting man?"

And he essentially said, "You know, you put your money down and you take your chances."

NARRATOR: Soon the results came in-- Judy was pregnant.

JUDY: We can't be this lucky.

This could not be happening to us.

This is like winning the lottery.

You know, one in a million, or whatever it is, and we just happened to be that one couple.

Can you tell yet what sex it's going to be?

Is it still too early?

Right now it's probably still too early.

In another three weeks, we might be able to tell.

NARRATOR: Judy's pregnancy was remarkably ordinary until a sonogram raised concern.

As she approached term, her head size began to fall to the lower limits of normal.

We were concerned that this slowing of the head growth might be associated with general abnormalities.

Georgeanna kept saying, "Don't worry.

"Judy's small and Roger's small.

"It's going to be a small baby.

Don't be nervous about it."

NARRATOR: For the next month, Howard Jones could not shake his fear.

In the tense hours before the scheduled cesarean birth, he planned for the worst.

I had written out a press release, which said that the baby had been born, that there was an abnormality, we were distressed about this, we hoped that the privacy of the patient would be regarded.

NARRATOR: As he entered the delivery room on December 28, 1981, Howard Jones folded the press release into his pocket.

(chattering) At 7:46 a.m., America's first test tube baby was born.

You're going to feel a pushing on you, is that okay?

NARRATOR: Weighing five pounds, 12 ounces, she was much bigger than the sonogram had indicated, and in perfect health.

The Carrs named her Elizabeth.

ROGER: All right, ladies, here she is-- Elizabeth!

Oh, she's doing great.

Hello!

Hello!

(laughs) MAN: The announcement itself was made by Dr. Howard Jones.

JONES: This morning at 7:46, a daughter was born to Mrs. Judith Carr, a 28-year-old school teacher.

The father is Mr. Roger Carr, a 30-year-old mechanical engineer.

JUDY: Not only was she perfect and normal, she had full head of hair and, you know, healthy, healthy looking and very pink and... and everything you hope for.

MARSH: When Elizabeth Carr was born, it emboldened other medical centers to go ahead and start up their own IVF clinics and to say to the federal government, "We're not going to worry about getting your money for this; we're going to risk it."

NARRATOR: Over the next two decades, Howard and Georgeanna Jones would continue to perfect in vitro fertilization and train the first generation of IVF doctors in the United States.

Okay.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: By 1985, 115 children owed their existence to the Joneses.

JUDY: The first baby reunion was perhaps the most special to me.

The staircase was just filled with parents holding their babies.

And to see all those couples with those beautiful babies, that's the first time it hit me just what had happened over the course of the past five years.

♪ ♪ HENIG: It was a little surprising how quickly people got used to IVF.

But not really, if you think about how people get used to all sorts of new technology.

That's sort of the pattern that it takes is that at first it seems like it's abhorrent and it's something that we absolutely shouldn't do.

And then for a while it seems kind of miraculous.

(children laughing) And then after a while, the technology just becomes part of the fabric of daily life.

(children laughing) In 1983, ten years after he stopped Landrum Shettles' experiment, Raymond Vande Wiele becomes the co-director of the first IVF clinic in New York City.

It's not because he was a hypocrite, or even because he changed that much.

It's because society changed and IVF became just the next thing to do for infertile couples.

♪ ♪ CAPLAN: Clinics popped up all over the place.

Some programs would put eight embryos back at a time, to try and get a better success rate.

Other places would say, "That's immoral.

We're only going to use three."

Some people would treat gay people.

Some people would treat single moms.

So the whole field wound up being a kind of wild, wild west where the free market reigned.

GEORGE: The doctor who gave us Louise Brown recalled looking at her in the Petri dish, and said, "She was beautiful then, and she's beautiful now."

There are really very deep and fundamental differences between Americans about some fundamental ethical questions: how we regard the human being, how we regard human life.

We are not united as a people on these questions.

NARRATOR: Since the birth of Elizabeth Carr, over 400,000 IVF babies have been born in America.

There are now more than two million "test tube" babies in the world.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Trailer | Test Tube Babies | American Experience

When the first human egg was fertilized in a lab in 1944, the news spread like wildfire. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCorporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.